Set 5 State Space Models

An alternate framework for time series modeling is the state space model. This model contains a lot of depth and flexibility. For additional model details, see this resource. These models are based on a decomposition of the series into a number of components, each of which may be accompanied by error terms (and thus, uncertainty). The simplest model is the local level model.

5.1 Local Level Model

In this model,

\[\begin{align} y_t &= \mu_t + \epsilon_t \\ \mu_{t+1} &= \mu_{t} + \eta_t, \end{align}\]

where \(\epsilon_t \sim N(0, \sigma^2_{\epsilon})\) and \(\eta_t \sim N(0, \sigma^2_{\eta})\). The idea of this model is that the observations \(y\) consist of noisy measurements (observation error) of an underlying random walk.

What is the estimate for \(\mu_t\) when \(\text{Var}(\eta_t) = 0\)? How about when \(\text{Var}(\epsilon_t) = 0\)?

5.1.1 Likelihood Function

We will first discuss the estimation of the parameters \((\sigma^2_{\epsilon},\sigma^2_{\eta})\) using maximum likelihood estimation.

\[\begin{align} p(y_1, \ldots y_n | \sigma^2_{\epsilon},\sigma^2_{\eta}) &= \prod_{t=1}^T p(y_t | y_{1:t-1}, \sigma^2_{\epsilon},\sigma^2_{\eta}) \end{align}\]

Each observation \(y_t\) given the past observations and states follows a normal distribution where,

\[\begin{align} y_t | y_{1:t-1} \sim N( E(\mu_t | y_{1:t-1}), Var(\mu_t | y_{1:t-1}) + \sigma^2_\epsilon ) \end{align}\]

5.1.2 Kalman Filter

The Kalman Filter provides a recursive way to estimate the state, \(E(\mu_t | y_{1:t-1})\), and its variance, \(Var(\mu_t | y_{1:t-1})\), recursively using the observations \(y_t\).

We will start by defining the prediction distribution as,

\[\begin{align} p(\mu_t | y_{1:t-1}) \sim N(a_t, p_t) \end{align}\]

The Kalman Filter takes this as given and then recursively updates

\[\begin{align} p(\mu_t | y_{1:t}) &\sim N(a_{t|t}, p_{t|t}) \\ p(\mu_{t+1} | y_{1:t}) &\sim N(a_{t+1}, p_{t+1}) \end{align}\]

To find the first distribution, \(p(\mu_t | y_{1:t})\), we define \(v_t = y_t - a_t\) and re-write,

\[\begin{align} p(\mu_t | y_{1:t}) &= p(\mu_t | y_{1:t-1}, v_t) \\ &= \frac{ p(\mu_t , v_t| y_{1:t-1})} { p(v_t| y_{1:t-1}) } \\ &= \frac{ p(\mu_t | y_{1:t-1}) p(v_t| y_{1:t-1} , \mu_t )} { p(v_t| y_{1:t-1}) } \\ &\equiv N(a_{t|t}, p_{t|t}), \end{align}\]

where

\[\begin{align} a_{t|t} &= a_t + k_t v_t \\ p_{t|t} &= k_t \sigma^2_\epsilon \\ k_t &= \frac{p_t}{p_t + \sigma^2_\epsilon} \end{align}\]

And, finally,

\[\begin{align} p(\mu_{t+1} | y_{1:t}) \sim N(a_{t|t}, p_{t|t} + \sigma^2_{\eta}) \end{align}\]

# Define the log-likelihood function for the Local Level Model

llm_log_likelihood <- function(params, y) {

# Extract variance parameters from params

sigma_eta2 <- params[1]

sigma_eps2 <- params[2]

# Number of observations

T <- length(y)

a_t_t <- 0 # Initial state estimate

P_t_t <- 10000 # Large initial variance (diffuse prior)

# Log-likelihood accumulator

log_likelihood <- 0

for (t in 1:T) {

# Prediction step

a_t <- a_t_t

P_t <- P_t_t + sigma_eta2

# Observation prediction

F_t <- P_t + sigma_eps2

v_t <- y[t] - a_t # Prediction error

# Update step

K_t <- P_t / F_t # Kalman gain

a_t_t <- a_t + K_t * v_t

P_t_t <- (K_t) * sigma_eps2

# Contribution to log-likelihood

log_likelihood <- log_likelihood - 0.5 * log(2 * pi * F_t) - 0.5 * (v_t^2 / F_t)

}

return(-log_likelihood) # Negative log-likelihood for minimization

}Next, we will simulate some data from this model and estimate parameters.

The MLE for \(\hat{\sigma}^2_\eta=\) 1.02 and for \(\hat{\sigma}^2_\epsilon=\) 2. These are very close the the true values of the parameters used to generate the data, offering some evidence the algorithm is working.

5.1.3 Forecasting

For a local-level model, the forecast for \(h-\)steps ahead is the most recent estimated level, \(\hat{\mu}_T\), since the model assumes the level evolves with a random walk.

The forecast variance accumulates uncertainty from the process and observations noise:

\[\text{Var}(\hat{y}_{T+h}) = \sigma^2_\epsilon + h \sigma^2_\eta\].

5.2 Bayesian Inference

5.2.1 Bayesian logic

In the Bayesian paradigm, parameters (\(\theta\)) are random and data (\(y\)) are fixed. Inference is carried out through the posterior distribution of parameters given data.

\[p(\theta \vert y) = \frac{p(y|\theta) p(\theta)}{p(y)}\] For very simple models, we can write the analytical solution for the posterior. For example, suppose we are flipping a coin and we are interested in learning about the parameter \(\theta = P(\text{Heads})\).

Before observing any data, we believe that \(\theta\) is probably around 0.5 but we are not sure. We can encode this belief with a prior distribution whose expected value is 0.5 and ranges from 0 to 1. A good choice is the Beta distribution. In particular, we can use a Beta(\(\alpha = 2\), \(\beta = 2\)),

\[\begin{align} p(\theta) = 6\theta (1-\theta). \end{align}\]

Now we generate some data. We flip the coin (independently) 7 times and observe 5 heads. Since our data is a sequence of 0s and 1s, we can use the binomial distribution for the likelihood. That is:

\[\begin{align} p(y_1, \ldots y_7 \vert \theta) &= {7 \choose 5} \theta^5 (1-\theta)^2. \end{align}\]

Now we can multiply them together to get the posterior distribution of \(\theta\):

\[\begin{align} p(\theta \vert y) &= \frac{p(y|\theta) p(\theta)}{p(y)} \\ &= \theta^5 (1-\theta)^2 \times \theta (1-\theta) \times 6/p(y) \\ &= \theta^6 (1-\theta)^3 \times 6/p(y) \\ &= \text{Beta}(7,4) \end{align}\]

5.2.2 Monte Carlo Idea

Suppose we can sample from \(p(\theta \vert \text{data})\). Then we could generate,

\[\begin{align} \theta^{1},\ldots,\theta^{S} \sim p(\theta | \text{data}) \end{align}\]

and obtain Monte Carlo approximations of posterior quantities:

\[\begin{align} E(g(\theta) \vert \text{data}) \approx \frac{1}{S} \sum_{i=1}^S g(\theta^i). \end{align}\]

But what if you can’t sample from \(p(\theta \vert \text{data})\)?

5.2.3 Metropolis Algorithm

The metropolis algorithm proceeds as follows:

Sample \(\theta^{\star} \sim J(\theta \vert \theta^{s})\), where \(J\) is called the proposal distribution. For the Metropolis Algorithm, we assume that this distribution is symmetric.

Compute the acceptance ratio, \(r\):

\[r = \frac{p(\theta^\star \vert \text{data})}{p(\theta^{s} \vert \text{data})}\] 3 Let

\[\begin{equation} \theta^{s+1} = \begin{cases} \theta^{\star} & \text{with prob min}(r,1) \\ \theta^{s} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{equation}\]

Step 3 can be accomplished by sampling \(u \sim \text{Unif}(0,1)\) and setting \(\theta^{s+1} = \theta^\star\) if \(u < r\) and setting \(\theta^{s+1} = \theta^s\) otherwise.

5.2.4 Example

Let’s consider a multivariate linear regression model. That is, we will model our response variable, \(y\), as

\[\begin{align} y = X\beta + \epsilon. \end{align}\]

For simplicity, let us assume that \(\epsilon \sim N(0,1)\). Therefore, the parameter that we want to do inference on is \(\beta\). So, we want to sample from \(p(\beta \vert y)\).To do so, we need two ingredients, a likelihood function and a prior distribution for \(\beta\), \(p(\beta)\).

\[\begin{align} p(\beta \vert y) &\propto p(y \vert \beta) p(\beta) \\ &= \text{likelihood} \times \text{prior} \end{align}\]

For the linear regression model, our likelihood function can be written as,

\[\begin{align} p(y \vert \beta) = (2\pi \sigma)^{-n/2} \exp{\bigg( -\frac{1}{2 \sigma^2} (y - X \beta)^T (y - X \beta) \bigg)}. \end{align}\]

For the prior, we will assume that we know nothing about \(\beta\). So, we will use the prior distribution,

\[\begin{align} p( \beta) \propto 1. \end{align}\]

We will use the proposal distribution,

\[\begin{align} J(\theta^{\star} \vert \theta) \sim N(\theta, cI) \end{align}\].

Let us start by sampling some data that follows this model.

set.seed(1)

n = 100

X = matrix( data = c(rep(1,n), rnorm(n) ), ncol = 2)

beta_true = c(1,2)

y = rnorm(100, mean = X %*% beta_true, sd = 1)Now let’s implement the MH algorithm and sample from the posterior distribution of \(\beta\). Our MCMC output for the slope coefficient, \(\beta_1\), is summarized below.

nIter = 1e5

betas = matrix(0, nrow = nIter, ncol = 2)

beta_current = betas[1,]

p_current = exp ( -1/2 * t(y - X %*% betas[1,]) %*% (y- X %*% betas[1,] ))

for(j in 2:nIter) {

# propose a new value for betas

beta_prop = rnorm( 2, mean = betas[(j-1),], sd = .2)

# compute probability of data | beta proposed

p_prop = exp ( -1/2 * t(y - X %*% beta_prop) %*% (y- X %*% beta_prop ))

r = p_prop/p_current

if ( r > 1 ) {

beta_current = beta_prop

p_current = p_prop

} else if (runif(1) < r) {

beta_current = beta_prop

p_current = p_prop

}

betas[j, ] = beta_current

}

5.2.5 Specific Problem

For the more general state space model we will use the package bsts.

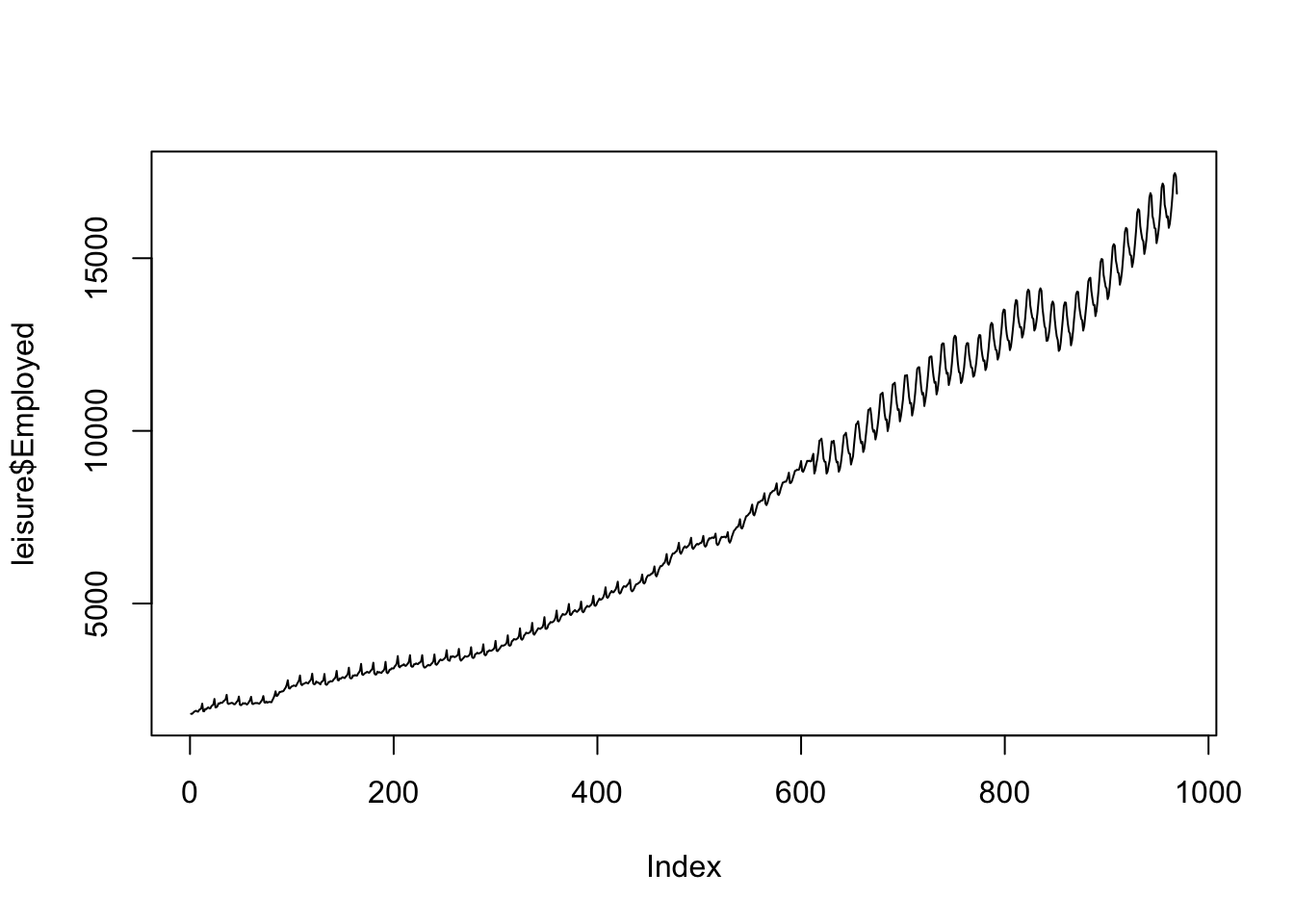

For our problem, we will introduce the covariate into the measurement equation. Our model is,

\[\begin{align} y_t &= \mu_t + \beta x_t + \epsilon_t \\ \mu_t &= \mu_{t-1} + \eta_t. \end{align}\]

We will use the package bsts to fit this model. The first thing to do when specifying a bsts package is the specify the contents of the latent state vector \(\mu_t\)